|

|

I created this site as a tribute to János Sebestyén, a musician of amazing versatility who has enriched my life and expanded my musical horizons for more than forty years. Sebestyén is remembered in his native Hungary for his hundreds of recitals and countless radio and television broadcasts. In other parts of the world he is recognized for his many recordings.

I discovered his art for myself in July 1979 on a fortuitous Friday the 13th. I was thirteen years old and had recently come across the score for Bach's Italian Concerto at my local library in Spirit Lake, Iowa. Anxious to hear this work, but with little to spend (having depleted my financial resources the week before on Gustav Leonhardt's traversal of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos), Sebestyén's Bach recital on the budget Turnabout label was my only option. This ubiquitous album, with its bright orange cover, was readily available even in small-town record shops of the Midwest. Already confident that I knew what a good harpsichord should sound like, I was somewhat disappointed by the woolly, jangling tone of the instrument heard on this recording. The music, however, was so engaging that I could not stop listening, and there was a natural musicality in Sebestyén's playing that I found appealing – it simply sounded right to me. I loved the intensity of his Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, the solemnity of the Toccata in C minor, and the high spirits of the Italian Concerto. Curious to hear more from this artist, I began to acquire his other Vox recordings. While the instruments played were not ideal and the performances sometimes careless, these LPs opened up a world of unfamiliar repertoire, spanning Polish renaissance tablature through the organ works of Liszt. I eventually began to acquire his Hungaroton recordings, and these were of significantly higher quality than those offered by Vox. His album of concertos by Cimarosa and Seixas was released late in the summer of 1983 and became an immediate favorite, clearly demonstrating the many qualities I appreciate in his playing. That fall, while visiting the music library of a local university, a reference book provided me with his famous Budapest address: Fillér utca 48. I wrote a letter and was excited when just after Christmas I received his reply. I decided then that I would attempt to collect all of Sebestyén's recordings.

|

|

The Bach recital for Turnabout, my first encounter with Sebestyén. |

|

Cimarosa and Seixas for Hungaroton, one of Sebestyén's finest recordings. |

|

Haydn and Handel for Angelicum, Sebestyén's first record published in Italy.

|

|

About half of Sebestyén's recordings were produced in Hungary for the state label Hungaroton. The other half came about as the result of his friendship with Thomas Gallia and Paul Déry, two colleagues from his earliest days at Hungarian Radio who later became prolific record producers in Italy. Gallia was born in Budapest to a prominent musical family – his grandfather, István Thomán, studied piano under Liszt and was later Bartók's teacher. He studied both music and engineering and his career began in 1947 at Hungarian Radio. In 1951 he became chief engineer for MHV, the predecessor of Hungaroton. After the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 he worked in Paris for Pathé Marconi then Disques Charlin, and from 1961 he was director of the recording studio at the Angelicum in Milan. Déry was born in Szeged. He worked as a producer at Hungarian Radio, then later performed with the Honvéd Art Ensemble. His passion was opera, and after 1956 he sang leading tenor roles in East Germany for several years. He later moved to Milan, where he was initially employed as a copyist for the music publisher Ricordi. It was during this time that Gallia established Sonart, his own freelance recording company, and Déry soon partnered with him in this venture.

|

|

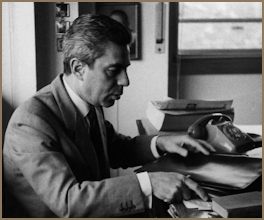

Thomas Gallia. |

|

Paul Déry.

|

|

Sebestyén's first visited Italy in 1963 and in October that same year was invited to play a concert with the Angelicum Chamber Orchestra in Milan. Concertos by Haydn and Handel were performed, and both works were recorded by Gallia for the Angelicum label. This was Sebestyén's first recording published outside of Hungary. In 1967 Gallia traveled to New York in order to establish a working relationship with George Mendelssohn, the Hungarian émigré and founder of the Vox label. Mendelssohn accepted Gallia's offer to produce recordings through Sonart, and upon the recommendations of Gallia and composer Miklós Rózsa, Sebestyén was engaged as soloist. Mendelssohn offered Sebestyén an exclusive contract, but Gallia, already familiar with Mendelssohn's legendary frugality, felt this would only limit their opportunities. Sebestyén's first marathon session with Gallia began in February 1968, resulting in eight LPs: four for Vox and four to be licensed by Sonart. This pattern continued during the summer and the following year. Technical aspects of the productions were managed by Gallia, while Déry assisted as producer and editor, his patient nature balancing Gallia's sometimes tempestuous personality. Each recording was rushed out of necessity and often completed in one or two days. Organs in Milan, Rovigo, and Brescia were utilized, while the harpsichord sessions took place at the Angelicum studio. Mendelssohn did not provide for the rental of a better instrument, so the studio's Neupert had to suffice. Sebestyén's compensation of $150 for each Vox recording was not particularly generous, while the Sonart recordings were made gratis out of friendship to Gallia. Mendelssohn did, however, assist Sebestyén in acquiring his first and only harpsichord, a Sperrhake. Despite the limitations, the resulting recordings were remarkably successful and the reviews often positive. The Vox recordings received worldwide distribution, while the Sonart recordings were published in Italy and France by Angelicum, CBS, Ariston, and BAM. These initial efforts to establish Sonart proved successful and by the 1970s Gallia and Déry were producing more than a hundred recordings each year for leading early-music artists and labels. Their collaborations with Sebestyén continued into the 1990s. Déry died in 1992 followed by Gallia five years later. Their passing marked the end of Sonart as well.

|

|

Thomas Gallia and Paul Déry, with compatriot Tibor Kelemen, at work in the control room of the Angelicum studio, 1968.

|

|

The first LP of Bach toccatas for CBS Italiana, one of many recordings Sebestyén made at the Angelicum studio.

|

|

Listen to Sebestyén discuss his experiences making records in Italy during an interview with music historian Allan Evans in New York on 23 May 1990. |

| |

|

|

|

Sebestyén's first recording of Bach toccatas, produced by Sonart for CBS Italiana in 1968, received favorable notices from critics and helped establish his career in Italy. |

| |

|

|

|

Through conversations with Sebestyén, I learned that his recordings were, for him, a small and not particularly important aspect of his career. He devoted most of his energy to concerts, which took him to more than twenty-five countries around the world. His close friendship with many music-loving diplomats serving in Budapest resulted in concert invitations from throughout Europe and Asia. Sebestyén's live performances were markedly different from his recordings, and it was for an audience that he played with almost fearless abandon. During the 1960s his harpsichord recitals were predominate, but by the early 1990s he devoted himself primarily to the organ and piano, his self-professed romantic temperment better suited to these instruments. Expectations regarding harpsichord performance had also changed to a historically-informed style, and his colorful manner of playing was no longer in fashion. He made a final harpichord tour of northern Italy in 1990, Sperrhake in tow, and afterwards only occasionally returned to the harpsichord for concerts and radio broadcasts in Hungary.

Like several performers from his generation, Sebestyén did not actually set out to become a harpsichordist – it came about through circumstance. As a student he studied composition, piano, and organ, with the latter his preferred instrument. In Stalinist Hungary of the early 1950s, however, opportunities for organists were limited, and in 1957 he was asked to play the harpsichord for a performance of Frank Martin's Petite symphonie concertante. This concert brought about a renewed interest in the instrument, unfamiliar to many in Hungary at that time, and inspired new works from several composers. Sebestyén was soon recognized as a harpsichordist and he endeavored to promote the instrument as a viable medium for more than just early music, demonstrating this with his first solo recording in 1963 by including transcriptions of piano works by Prokofiev and Frank Martin and a new composition by Emil Petrovics. His harpsichord recitals often included his own adaptions of piano compositions by friends and colleagues.

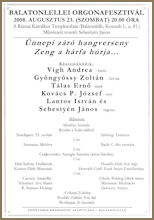

One aspect of Sebestyén's art, known primarily to those who attended his concerts, was his gift for improvisation. Whether performing as pianist or organist, on the large romantic organ in Pécs or the small ancient organ in Sion, he had the ability to exploit the resources of any instrument at his disposal in the style of his choice. His partners in improvisation included pianist Geoffrey Tozer, flutist István Matúz, soprano Laura Faragó, and bassist Aladár Pege. Special mention, however, must be made of his more than twenty-five year collaboration with István Lantos, performing compositions and improvisations for two pianos, piano four-hands, and organ four-hands. In later years they often collaborated with tenor Ernő Tálas and flutist Zoltán Gyöngyössy. These three musicians, along with actor József P. Kovács, became Sebestyén's go-to team during his last decade, always finding time to take part in his regular concerts in Budapest, Balatonlelle, and Szeged. It was thanks to their devoted friendship that he was able to continue performing during his final years of declining health.

|

|

Balatonlelle concert, 2008. |

|

Sebestyén's devoted musical collaborators: tenor Ernő Tálas, pianist and organist István Lantos and flutist Zoltán Gyöngyössy, 2009.

|

|

Live broadcast from Hungarian Radio with Gábor Dombóvári, 2001. |

|

Harpsichord lesson at the Academy of Music with

Mónika Kecskés, 2003.

|

|

Besides his concert and recording activities, there were two other important facets to Sebestyén's career: radio and teaching. From 1950 he worked for Hungarian Radio in multiple capacities and for forty-five years wrote and hosted several popular programs including Those Radio Years, From the Diary of a Radio Reporter, and Wings of Memories. These broadcasts began in 1962, documenting culture and politics throughout the past century. Sebestyén was at heart a radio man, and this was his passion from a very early age. He also appeared regularly on Hungarian television, famously hosting the annual New Year's Concert from Vienna for thirty-five years, and the series Zene-Óra featured interviews and performances by musician friends including György Sándor, Aldo Ceccato, Zuzana Růžičková and György Pauk. In 1970 he established the first harpsichord class at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music, securing for the instrument a permanent place in Hungarian musical life. He served as professor until 2009 and his many successful students include Szilvia Elek, Zsuzsa Elekes, Péter Ella, Anikó Horváth, Desző Karasszon, Judit Péteri, Hédi Salánki, András Szepes, Miklós Spányi, and Ágnes Várallyay.

János Sebestyén understood the architecture of music. His strongly rhetorical interpretations could find drama and meaning in the most unlikely of places, turning a simple Bach prelude into a work of significance. As author Allan Evans so aptly observed, "This vivid spirit somehow unscrambled works sounding vague in the hands of others." From my first encounter with his playing, I also sensed the presence of a very real, sometimes fallible, musician and human being. Perfection was rarely his objective, and this very aspect of his playing, curiously enough, encouraged me to listen even more carefully. Sebestyén never understood why I enjoyed his recordings and often joked there had to be something wrong with my hearing. In the end, however, I believe he was grateful that I listened.

|

|

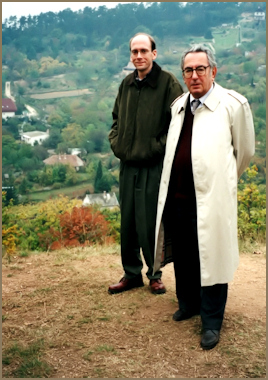

Robert Tifft and János Sebestyén

on a walk in the Buda hills, 2001. |

|

Robert Tifft

Dallas, Texas

Email Email

Thanks to many friends for their contributions to this site:

Paul Gabler, Marco Papi, Arnaud Nader, Dénes Csiky, Éva Györki, Lászlo Terdik, Ágnes Várallyay, Máté Hollós, Péter Herke, Judit Hidasi, Éva Thomán Juhos, Judit Péteri, Angela Tosheva, Dorothy Armstrong, Richard Young, Zuzana Růžičková, Anikó Horváth, Zoltán Paul Jeney, Kate Wacz, Allan Evans, Sándor Mátyus, Lóránt Kovács, Ecaterina Botár, David Roblou, Marco Taio, Miklós Spányi, and special thanks to Ágnes Ivánffy and Paul Uhler for making my visits to Budapest possible.

|

|