|

|

A Short History of Harpsichord Playing in Hungary

|

|

Allow me to extend a hearty welcome to the jury, sponsors and competitors of the first Hungarian harpsichord competition, and to all those interested in the special sound of this instrument and the great variety of masterpieces, both historic and contemporary, to be performed on harpsichord.

The twentieth-century revival of the harpsichord was associated with the name Wanda Landowska from the earliest years of the century onward (with the possible exception of Violet Gordon Woodhouse in England). The Pleyel instrument she designed served as a model for the firms Neupert, Wittmayer and others for building their "pedal" harpsichords. Landowska's students who carried on her teaching were Eta Harich-Schneider in Germany, Silvia Kind in Switzerland, Ruggero Gerlin in Italy, and Ralph Kirkpatrick in the United States, though the latter as her opponent. There were a few harpsichordists independent of Landowska, but their role was rather experimental, the by-product of the art of organists and pianists. On the whole, the harpsichord was like a "Sleeping Beauty" in most countries.

In Hungary, the splendid organist and music historian, János Hammerschlag, turned to early music. He had no instrument, but issued publications on ornamentation and wrote an article entitled The Soul of the Harpsichord for the periodical Crescendo in 1928.

Wanda Landowska visited Budapest in the early 1930s and gave a recital at the so-called Town Theater. Hammerschlag got in touch with her on this occasion and consulted Eta Harich-Schneider by way of correspondence, but in the absence of a harpsichord, nothing else could happen. There existed, as a matter of fact, two harpsichords in private property in Budapest, but they never appeared on the concert stage. One of them was a grand Pleyel designed by Landowska and owned by the pianist Mrs. Erzsébet Láng Kecskeméti, who is mentioned in Bartók's correspondence. She moved to the United States before the war broke out and took the instrument with her. As a matter of curiosity, let me mention that the actress Judit Bretán, daughter of Nicolae Bretán, the eminent composer and member of the Hungarian Theater at Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca), later got hold of this famous instrument. Its subsequent fate in the United States is unknown. The other harpsichord belonged to the music historian Ferenc Brodszky, an eccentric Hungarian scholar who maintained contact almost exclusively with Hammerschlag. He showed his instrument in private once or twice and put it at Hammerschlag's disposal some time in 1950 when the organist gave an early music course at the Academy of Music. This is the first time that a harpsichord turned up within the walls of the Academy.

The only "official" harpsichord came to Hungary in 1944 – allegedly brought by the German occupation army in order to accompany the recitatives of Mozart's operas. According to another source, the harpsichord had earlier been in the possession of the Hungarian Opera. This heavy-duty, iron-framed instrument of piano-like touch appeared on the concert stage as the only "state-owned" harpsichord of the mid-fifties.

|

|

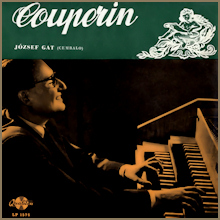

József Gát's 1961 Couperin recital was the first Hungarian LP devoted to the harpsichord.

Listen on YouTube >> |

|

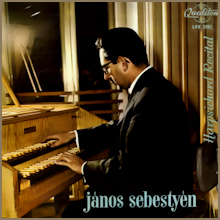

János Sebestyén's 1963 LP recital included works by Prokofiev, Martin, and Petrovics.

Listen on YouTube >>

|

|

Meanwhile, something happened on "private initiative" as well. Professor József Gát, a one-time student of Bela Bartók, who was teaching piano and methodology at the Academy of Music, became interested in early instruments. He acquired an Ammer harpsichord and, assisted by an engineer friend, tried to install a discreet amplifier that touched the strings - similar to the guitar - so that there was no need for a complicated solution with microphone. To support the experiment, Neupert also provided an instrument. There later surfaced a spinet and a clavichord. This collection of instruments was then presented by József Gát in the great hall of the Academy of Music in 1955. Thus, the introduction of harpsichord culture to Hungary was associated with the name of József Gát. Although he concentrated on methodology all his life, he had an excellent sense for style and was familiar with the "soul" of the harpsichord. He rarely appeared on stage, but luckily enough the Hungarian recording company recorded with him Bach's Goldberg Variations in 1963 and works by Couperin in 1961 and 1966. József Gát died at the early age of 54 in 1967. His book The Technique of Piano Playing (1954), later translated into four languages, was the first publication in Hungarian to contain several pages devoted to the harpsichord and the development of early keyboard instruments.

The "state-owned" Pleyel harpsichord of the Opera House first appeared in public in the autumn of 1957. The Radio Orchestra conducted by György Lehel performed Frank Martin's Petite Symphonie Concertante for harpsichord, piano and harp, with the present author playing the harpsichord solo. The performance of Martin's work was attended by several composers who discovered the special sound of the harpsichord. Some months later Emil Petrovics composed the first Hungarian work for harpsichord with the title Four Masked Self-Portraits. Other composers started to use the harpsichord in film music – it was the time when the first Sputnik was launched, providing an excellent opportunity to present celestial sounds.

In Hungary, the harpsichord came increasingly into fashion in 1958. The present author popularized this instrument on the radio, in film studios and in the concert halls. It goes without saying that the heavy-duty Pleyel was carried everywhere. Its piano-like keyboard, along with my desire to show that the harpsichord was an instrument like any other, was a source of inspiration for performing the music of our century. Prokofiev's and Shostakovich's transparent works, Frank Martin's preludes, small pieces by Miklós Rózsa, and several other arrangements could be performed on the Pleyel. Meanwhile, the state musical institutions – practically under complete state control in those days – showed increased interest in the harpsichord, and so the first large instrument, Ammer's five-pedalled Bach model harpsichord, arrived in the country by 1959. As the Ammers built musical instruments in the one-time German Democratic Republic, it was the only possibility to acquire a harpsichord for "eastern" currency. The first instrument was ordered by the National Philharmony; its example was followed rapidly by Hungarian Radio and the recording company. No other town had money for such procurements, and a private acquisition was out of the question due to the extremely strict monetary regulations that prohibited the private property of even eastern socialist currencies.

|

|

János Sebestyén's mother, Rózsi Mannaberg, trying out a new Ammer harpsichord in their home, 1967. |

|

Paul Gerstbauer, Steinway representative from Vienna, in Budapest with his wife Emma, 1967.

|

|

In 1967 a certain détente could be felt. It was then that Paul Gerstbauer, the Austrian representative of Steinway, came to Hungary. He represented Sperrhake in Vienna, was an extremely flexible businessman and good friend. After assessing the financial conditions in Hungary, he offered that the settlement of accounts could be done at the beginning of the new "fiscal year" – during the remainder of the year nothing else could be ordered. In this way Hungarian Radio and the Philharmony got a "western" harpsichord. I also came into possession of an instrument in 1968 through "payment by installments" negotiated by the Vox Recording Company (New York). Earlier the harpsichords ordered by the above institutions had been in my home for two or three months for purposes of trying them out and "playing them in".

Thus the harpsichord collection gradually grew but there was still no education for it. Chance was instrumental in starting the training. In 1970 the world-famous violinist Dénes Kovács, rector of the Academy of Music at that time, and I recorded Corelli's sonatas using a hired harpsichord from Vienna. One night, after a recording session, we were walking home under the star-lit sky when the rector suddenly stopped and asked me: "Why is there no harpsichord training in Hungary?" "There are neither teachers nor instruments", I answered. As we walked on, he stopped again and said: "Let's buy an instrument then." Some time later he added: "I charge you to organize the department." This is how it started. Everything seemed completely easy... at least that night. Not the next day. It turned out that the foreign currency allotment was exhausted for that year. A month later Mr. Gerstbauer appeared with a trailer bringing a harpsichord "on credit". The harpsichord department of the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music started its work exactly thirty years ago this autumn.

|

|

Early days at the Academy of Music: János Sebestyén with students Ilona Sándor and Irén Pólya, circa 1975. |

|

Czech harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková, a regular visitor to Budapest, with violinist Vilmos Tátrai, 1979.

|

|

I am convinced that musicians from well-to-do countries amply provided with period instruments must read this introduction to understand how many obstacles had to be overcome to realize things that seem so natural now. The narration could be finished at this point as matters started to take their own natural turn, even if by fits and starts.

But there is a coda left which is perhaps not uninteresting after all. I can claim without modesty that harpsichord culture has been radiating from the Academy of Music since that time, assisted by Hungarian Radio, which transmits not only the concerts faithfully, but also early music from recordings. In the second year of the department, Anikó Horváth, now a teacher at the Academy, won the second prize of the International Harpsichord Competition in Paris (the first prize was not awarded). Similarly, András Szepes won the Prague competition in 1999. In the intervening time, several harpsichordists took part in courses and symposia and received prizes (e.g. Ágnes Várallyay, assistant of the department, Rita Papp, and many others). Likewise, several professors came to the Academy to give mastercourses.

|

|

Harpsichordist András Szepes, winner of the 1999 Prague competition, with János Sebestyén and Zuzana Růžičková. |

|

The harpsichord faculty at the Academy of Music, 2002: János Sebestyén, Ágnes Várallyay and Anikó Horváth.

|

|

At the beginning the harpsichord department functioned optionally. This explains why Zsuzsa Pertis went to study with Isolde Ahlgrimm in Vienna or Borbála Dobozy with Zuzana Růžičková in Prague. In the second stage, the harpsichord department was associated with the piano department in the proportion of two plus three years. The third period permitted us to give a diploma to outstanding students (Miklós Spányi being the first), and finally, ten years ago, harpsichord was installed as a five-year training program with its own department. Basso continuo, baroque tuning and baroque chamber music were included among the subject-matters. Nevertheless, we do not concentrate entirely on early music, due partly to the restricted financial possiblities of the country and the Academy, which does not allow us to acquire a collection of baroque instruments. On the other hand, the name of Ferenc Liszt and the traditions of the Academy entail the training of many-sided musicians. The program of the present competition also meets these objectives.

After having established contacts with the firm Dowd of Paris, the Academy and other musical institutions in the capital were provided with Dowd instruments. Sassmann copies were also obtained. Unfortunately, the Hungarian orchestras and country towns are still using Lindholm instruments of extremely poor quality, produced in the one-time German Democratic Republic and meant to substitute for Ammer harpsichords.

In 1990 the state monopoly of organizing concerts ended. Numerous chamber orchestras and ensembles, including several devoted to early music, were founded. To stage a concert is now a matter of finances, which affects the supply of instruments as well. The prize of imported harpsichords is enormous. Now and then, Hungarian instrument-building experiments prove to be successful, but even such instruments are unattainable for students.

Members of the jury have all visited Hungary repeatedly; the pioneer was Zuzana Růžičková who first played here in 1959 and every year since then.

The harpsichordists not taking part on the jury include George Malcolm, who gave recitals here several times in the 1970s, Gustav Leonhardt, who played here more than once, and we must not forget either Huguette Dreyfus or Johann Sonnleitner.

The Early Music Days in Sopron form an essential part of Hungary's cultural life, the Early Music Forum in Budapest already has a certain tradition, and the Bach concerts organized at the Deák Square Lutheran Church enjoy increasing popularity.

It is high time to find out what we can offer with a competition, the First International Harpsichord Competition, Budapest. We do hope it will be a success. We are pleased about your support and welcome you warmly to Budapest in 2000.

János Sebestyén

|

|